September 2014

Regimes 'lack consistency'

Australian jurisdictions’ proportionate liability regimes significantly lack consistency, South Australian Supreme Court Justice Kevin Nicholson told the AILA Geoff Masel memorial lecture series hosted by branches around the nation.

He said the lack of consistency had created the “potential for undesirable and uncertain application of the principles and the capacity for contracting parties to engage in forum shopping”.

More than a decade after legislative implementation in jurisdictions throughout Australia, proportionate liability regimes still provoked debate within the legal profession and among industry stakeholders.

Judicial analysis, including by the High Court in Hunt & Hunt Lawyers v Mitchell Morgan Nominees Pty Ltd, provided significant guidance. But Justice Nicholson said problems arising from variations and inconsistencies across the jurisdictions, and in the operation of the regimes generally, persisted.

“There have been repeated calls for legislative reform in the hope of achieving a more uniform approach. There is already a significant body of commentary dealing with the proportionate liability regime,” he said.

Proportionate liability first appeared in some Australian jurisdictions for non-personal injury damages claims arising from building disputes.

One underlying motive was to protect the construction industry from the “deep-pocket syndrome” commonly associated with joint and several liability. The idiom describes the “quite understandable desire” of plaintiffs with claims involving multiple wrongdoers to pursue the defendant with the greatest financial backing on the basis they could be held accountable for the total loss. Justice Nicholson said such a defendant typically had a deep pocket because it held liability insurance. “Of course, it would not necessarily be the major contributor to the loss.”

In 2002, Australia’s second largest general insurer, the HIH Group, said to have held 35% of the professional indemnity market, collapsed. The lead up to and aftermath of the collapse became known as Australia’s insurance crisis, when increased pressure on the industry led to dramatic rises in premiums and unavailability of cover, posing serious difficulties for businesses and professionals seeking to obtain affordable liability insurance.

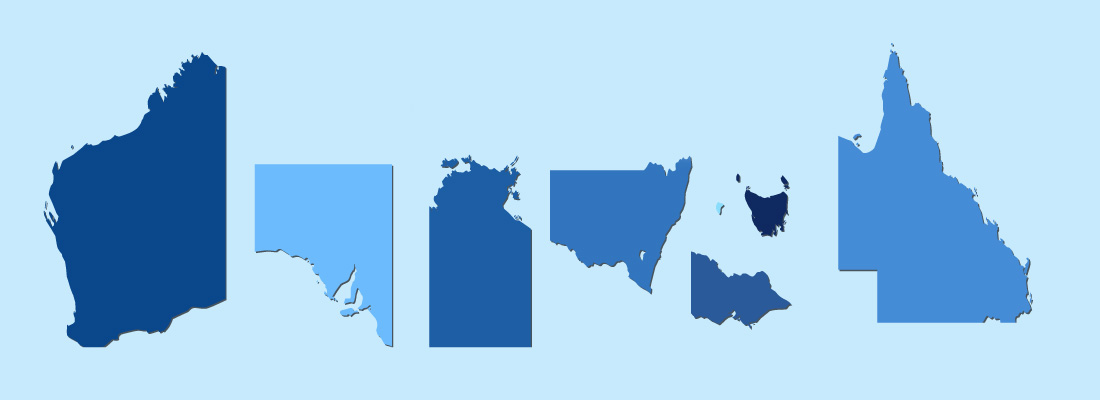

That was the climate in which statutory implementation of proportionate liability across Australia was pursued with renewed vigour. Proportionate liability schemes were introduced in varying forms across all Australian jurisdictions from 2003 onwards.

Justice Nicholson said courts in all Australian jurisdictions had to consider three questions when determining whether proportionate liability applied to claims:

1. Is the claim apportionable?

2. If yes, is the defendant a concurrent wrongdoer?

3. Is proportionate liability, for any reason, excluded from application?

If proportionate liability applied, the court’s task was to apportion liability in a way that reflected the responsibility of each wrongdoer.

“While the overarching approach to implementation might be very similar, if not the same, potentially significant variations in the legislation from jurisdiction to jurisdiction remain,” he said.

Defining apportionable claims

Proportionate liability applied only to apportionable claims. With the exception of South Australia and Queensland, such claims were defined in all jurisdictions (with slight variations) as a “claim for economic loss or damage to property in an action for damages (whether in contract, tort or otherwise) arising from a failure to take reasonable care” and “a claim for economic loss or damage to property in an action for damages” under the relevant legislative proscription(s) of misleading or deceptive conduct.

Justice Nicholson said the federal Trade Practices Act, Corporations Act and ASIC Act contained similar definitions for misleading or deceptive conduct. A claim for misleading or deceptive conduct would be apportionable, regardless of whether it involved a failure to take reasonable care or, as was the case in Qld, a breach of a duty of care.

The SA Act defined a liability as apportionable in terms of a claim involving negligent or innocent liability for harm, arising in tort, breach of contractual duty of care or under statute.

The Qld Act defined an apportionable claim in terms very similar to other jurisdictions but referred to claims for damages arising from a “breach of a duty of care” not a “failure to take reasonable care”.

Justice Nicholson said all state and territory jurisdictions excluded proportionate liability for claims “arising out of personal injury” and some jurisdictions expressly excluded the operation of proportionate liability where a defendant intended to cause loss or was fraudulent.

The jurisdictions diverged on the definition of “damages” for the purpose of an apportionable claim. In NSW, the Northern Territory, Qld, Tasmania and Victoria the definition of “damages” included “any form of monetary compensation”. SA defined “damages” as “compensation or damages for harm”. The ACT, Western Australia and federal regimes did not define “damages” for that purpose.

Contracting out

Justice Nicholson said there was no uniformity of approach in the ability of parties to contractually allocate risk by contracting out of proportionate liability regimes. Contracting out occurred where two or more parties reached a prior agreement about allocation of liability, if a claim arose, which differed from the result from the application of the relevant statute.

Parties sought to achieve it:

(i) by including a contractual provision that expressly provided that the relevant proportionate liability regime did not apply to any claim between the parties; or

(ii) by including a contractual provision that expressly provided for allocation of liability in a particular way, such as an express right of indemnity or an exclusion from liability.

The former, if effective, would return the parties (in the event of a claim made against more than one of them) to the common law position (as modified by statute) in force outside the proportionate liability regimes.

The latter approach, if effective, sought to identify, by agreement and in advance, where the risks were to fall. Justice Nicholson said both approaches had potentially significant ramifications for all parties to any such agreement, whether they end up being a plaintiff or a defendant to a liability claim.

Qld was the only jurisdiction that appeared to prohibit contracting out of proportionate liability. Although it was is implied rather than expressed. WA, NSW and Tasmania expressly permitted contracting out. The ACT, the Northern Territory, Victoria and federal legislation was silent. Justice Nicholson said SA took a different approach but one that may, in some circumstances, permit contracting out.

Key criticisms

In response to concerns about the differences between the jurisdictions’ proportionate liability legislation and uncertainties on the operation of some provisions, the Standing Committee of Attorneys General (SCAG) began a review of the legislative framework in 2006.

Justice Nicholson said it was undertaken in the hope of achieving greater uniformity across each jurisdiction and was in part conducted by commissioning two reports by Tony Horan and Professor Jim Davis.

The reports were used to develop consultation draft model provisions, released for comment in 2011. SCAG had now transmogrified into the Standing Council on Law and Justice (SCLJ), under whose auspices the review process had continued.

A decision regulation impact statement was released in October 2013. It identified two specific areas of concern with the operation of the nation’s proportionate liability regimes.

The first was the lack of consistency, particularly for contracting out. The concern was it encouraged parties to commercial arrangements to nominate the law of a particular jurisdiction as the governing law for a contract.

For proportionate liability, parties more likely to be plaintiffs in a given claim would want to contract out of the regime and might wish to nominate the law of a jurisdiction in which contracting out was permitted.

Defendants might prefer a jurisdiction where contracting out was not permitted. “That can be of real concern in commercial matters where there is a substantial imbalance in bargaining power between the contracting parties. There is the potential for more vulnerable defendants to be forced into surrendering the protection afforded by proportionate liability,” Justice Nicholson said.

A capacity to contract out presented difficulties for insurers in pricing risk. “If a particular insured is operating its business within a regime that permits contracting out, it will be difficult for that insured’s liability insurer to be able to assess the extent to which its insured might, during the period of cover, be exposed to claims made against it that would be regulated by the proportionate liability regime or by the pre-existing state of the law,” he said.

The problem was exacerbated by the lack of consistency between jurisdictions. The fact that parties can agree on the law of a particular jurisdiction to be the governing law for any dispute they may have in the future means they can, by agreement, render themselves bound to or freed from a proportionate liability regime, notwithstanding where the parties, the transaction and the project the subject of the transaction might be located.

Justice Nicholson said that would exacerbate an insurer’s difficulty in pricing risk for a particular insured in advance. “The capacity for a party with the greater bargaining power to impose on its weaker contracting parties a regime more favourable to the stronger party is enhanced.”

It was arguable the capacity to contract out of the regime(s) undermined the very policy objectives that gave rise to their introduction.

“On the other hand, the classical notion of freedom of contract, particularly when applied to large and complex projects where the parties might be seen to be in the best position to assess and allocate risks and to price the risks as part of the contractual considerations, is seen as a justification,” he said.

Justice Nicholson said perceived problems associated with the capacity to contract out and various options for reform were identified and explored at some length in SCLJ’s 2013 statement.

“One option not discussed at any length would be to attempt to limit or control the circumstances in which contracting out might be permitted,” he said.

“The control mechanism might be quantitative (based on characteristics, including size, of the project) or normative (based on an assessment of respective bargaining strengths, unconscionable conduct during the negotiation process and an assessment of the fairness of resulting contractual terms).

“As far as the latter is concerned, the statutory and unwritten law of unconscionable conduct already provides some protection. Perhaps it is enough and the power to contract out should be left alone,” Justice Nicholson said.