| HOME | NEXT |

Class action litigation broadening

By Resolve Editor Kate Tilley

Australia’s class action environment is now far more diverse than the traditional shareholder claims and far more sophisticated than even the US regime.

That’s the view of Herbert Smith Freehills Partner and class action specialist Jason Betts, who spoke at an AILA webinar chaired by David Lloyd, Regional Claims Manager Asia Pacific HDI Global SE.

Mr Betts said Australia had broadened beyond shareholder and investor class actions and corporate governance investigations and breaches. While those class actions still occurred, there were another four types of actions.

They were:

- Traditional product liability claims for faulty or defective manufactured products. Mr Betts said they were “enjoying something of a renaissance”, following a similar trend in the United States.

- Mass tort negligence class actions, often associated with natural catastrophes, with allegations against institutions or quasi-government instrumentalities for a lack of preparedness or remedial response to natural disasters. They included environmental toxic torts for land contamination. Mr Betts said there had been several prominent cases in recent years, prompted by a greater focus on environment, social and governance (ESG) standards.

- Employment-based class actions where a range of allegations might arise about how employees are paid, how they’re classified between employment and independent contractor status, their working conditions, and whether a workplace is free from discrimination and harassment. Mr Betts said the “bucket of employment claims is not necessarily growing but is a surprisingly healthy mainstay within the five species of litigation”.

- Consumer class actions have arisen in the shadow of bank litigation. “Any business that’s interacting with hundreds or thousands of touch points with consumers, selling products to a particular pricing model, that has a standard contract, or their supply of products is subject to particular consumer protection legislation, all fit within the rubric of consumer claims. That’s a real growth area,” Mr Betts said.

Diverse ecosystem

“It is important to think about class actions as being a diverse ecosystem. Shareholder claims are just one aspect of that.

“I’m a defence lawyer, so factor in all my biases, but Australia is a more plaintiff-friendly jurisdiction in the sense that it is far easier to [start] claims in Australia legally, putting costs to one side, than it is in the United States.”

Mr Betts said the Australian class action market was sophisticated and the advent of third-party litigation funding made it perhaps the most sophisticated globally. He said 28 litigation funders currently operated in the Australian market.

While funders were originally attracted more heavily to investor and shareholder claims, they were now searching entrepreneurially for “real estate” for more claims.

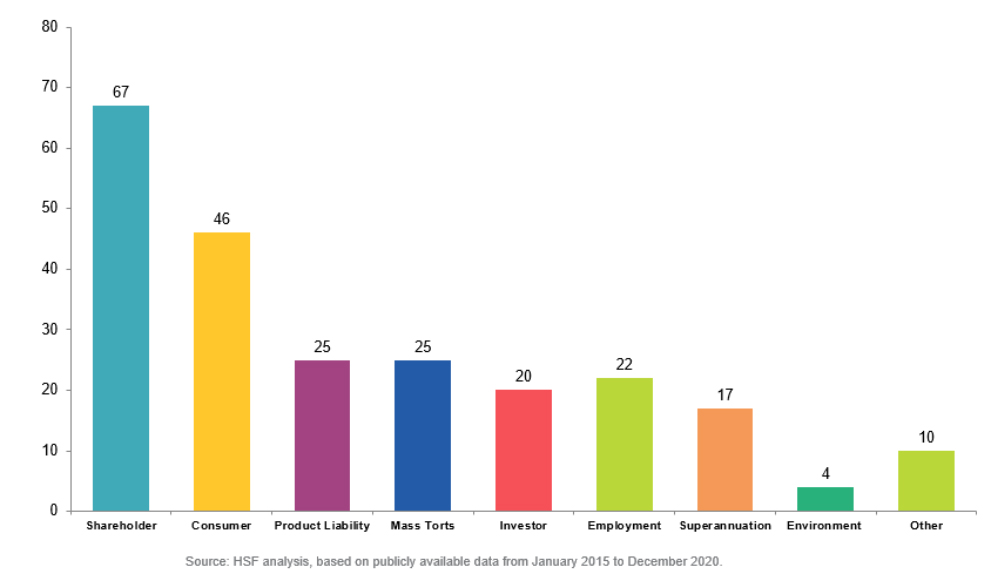

From 2015 to 2020, filings by claim type were:

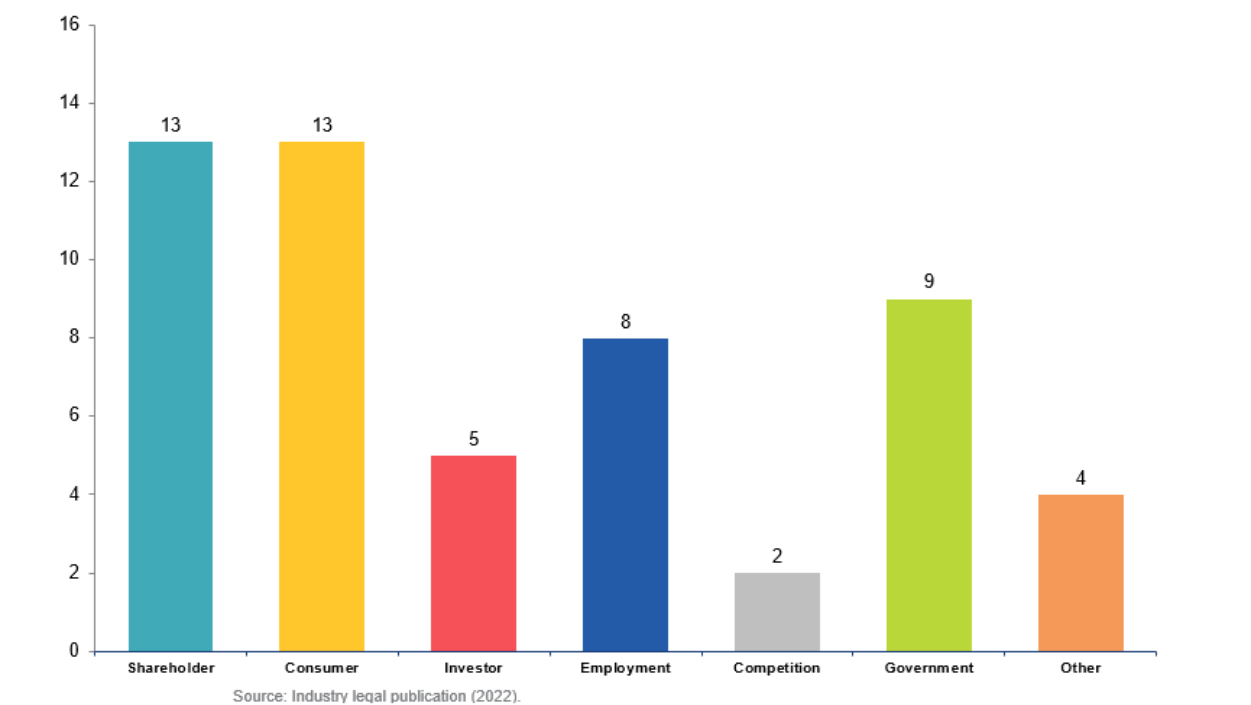

Class action filings by claim type for 2021-2022 were:

Mr Betts said consumer and shareholder class actions were “the two pillars of growth in class action litigation at the moment”. There was also a perhaps surprising trend line for government claims, because “we have seen a range of claims against government instrumentalities associated with environmental toxic torts and environmental claims associated with climate disclosures that have been made by governments, including in government-issued financial products”.

Emerging technology

Mr Betts said reasons for the “recalibration away from the heavy focus on shareholders and towards other areas of risk” were manifold.

“One is the growth of emerging technology and emerging products. Crypto assets, for example, are an area the law hasn’t caught up to yet. Are they financial products? Are they akin to shares? Are they a technology asset? What are the norms of law that will regulate how they’re traded? And what are the norms that will determine what you can say about that asset?”

A crowded shareholder class action market also prompted plaintiff lawyers and funders to seek other “real estate”.

Mr Betts said there had been “no political success … in placing major restrictions on the growth of class actions of any species”.

Contingency fees

Another factor fuelling growth was the Victorian jurisdiction adopting contingency fees.

Mr Betts said the Federal Court had historically been the preferred jurisdiction and consequently “judges of that court have developed extremely deep experience and competency”.

However, Victorian courts were likely to see an increase because of contingency fees, called group costs orders. The fees were “illegal in other states, as they’re seen as over-incentivising lawyers”.

He said litigation funders were attracted to the Australian market because it was a functional US-style litigation regime with reasonably certain normative standards, strict liability for misrepresentations, one of the world’s only true continuous disclosure regimes and strict product liability.

“Funding is an established part of our chain, but it’s been choppy waters. The courts have taken different approaches to funding.”

Early quantum

Mr Betts said insurers were “deeply sophisticated” in class action litigation, however, their “real challenge” was to get a sense of quantum early despite the group composition being “often completely unknown”.

“There’s no process by which interested or participating group members are required to come forward.”

Defence lawyers had to ascertain facts like the corporate state of mind in a product liability case. For example, “did the company know the product was defective? That’s going to have a major impact on potential damages.

“Should this be a settlement case or a trial case? Let’s make that call early. It’s a tough regime to achieve that.”

Mr Betts advises insurers and defence counsel to be transparent about the obstacles and seek ways to overcome them, but also have the patience to understand the average life cycle of a class action is three to four years.

“It’s hard to truncate that. The courts are saying the parties need to work on parallel tracks to try and get to the heart of the issues earlier. And the trouble is, without legislative change, that will not happen.”

Political support lacking

Asked whether courts were frustrated by the time frames, Mr Betts said “absolutely”.

“[Currently] there’s not a lot of political support for front loading or making the hard decisions early, like some form of certification process at the start of a case where the parties are required to grapple with quantum and have an early process for registering if you want to participate,” he said.

“None of that is easy to get political support for and you need that if we’re ever going to change the current state of affairs.”

Mr Betts said he was “not a fan of contingency fees”, however he expected them to become “a national phenomenon”. If so, “law firms theoretically become their own funders … and the frequency of filings will significantly increase”. He questioned “whether it is right for jurisdictions to be chosen according to lawyer remuneration?”

Resolve is the official publication of the Australian Insurance Law Association and

the New Zealand Insurance Law Association.